It is time to talk about hair and what it entails.

Starting from a sense of aesthetics, most men and women place value on personal appearance, and hair is a part of general grooming practice. Particularly for women, hair has historically quintessential been considered essential in regards to beauty, and they are subjected regularly to societal pressure in regards to the general aesthetics of their hair.

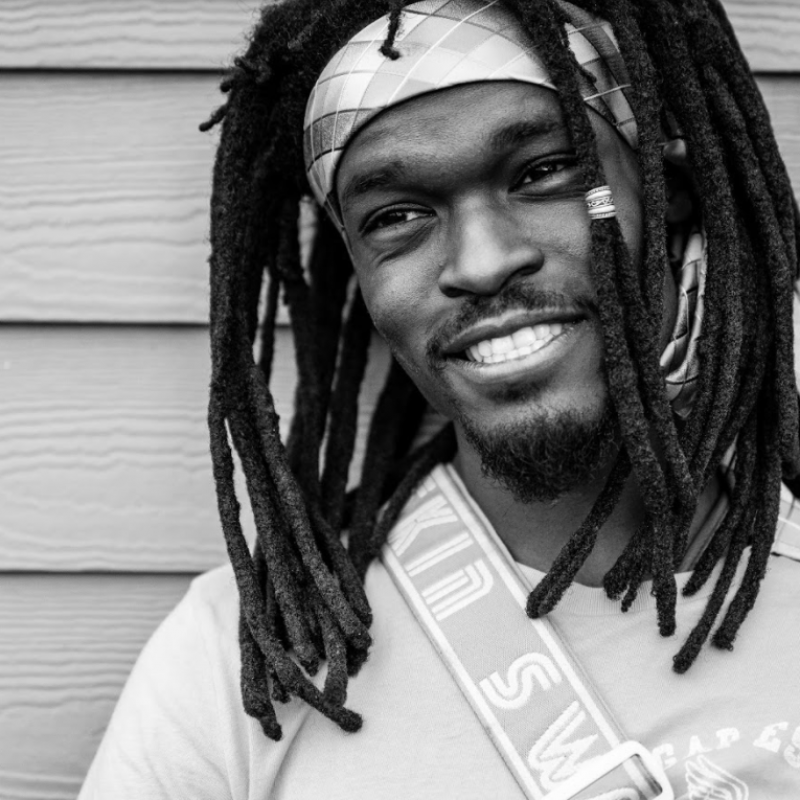

However, for Black people, hair is far more than just appearance. Black hair is not and will never be just hair.

Black hair is identity. It is beauty standards, professionalism, and discrimination at the workplace. It is cultural appropriation and colonialism. It is mental health, self-esteem, and history. It is flipping a coin during birth to know whether someone has “good” or “bad” hair and the humungous impact it will have for the rest of their lives.

What may be considered a vain, trivial subject for other races is something that can profoundly alter the way Black or Biracial folks navigate through life, the challenges they face, and the opportunities they may be able to enjoy.

In short, Black hair studies are a microcosm that allows analysts and everyday folk to see the full spectrum of the issues faced by Black and Biracial people worldwide through the angle of colonization, euro-centric beauty standards, and racism.

The complexity of Black hair and its ramifications within the study of Black sociology, politics, culture, and aesthetics require extensive study across the centuries and latitudes. Understanding the reality of Black hair and its interactions with the daily life of Black and biracial folks requires a throughout analysis of its journey.

But first things first—what is Black hair?

What does science say?

Understanding the hereditary nature of hair does not require any advanced studies. Aspects such as texture, shape, thickness, and density are prone to be inherited, therefore genetic, and subsequently intrinsically linked with race and ethnic backgrounds.

Despite this, ethnic studies of hair structure and genetics are relatively scarce and not particularly profound. Under this lens, the current ethnic hair classification recognizes three macro-categories: African, Asian, and Caucasian.

To the keen eye, it is clear this division is general, reductionist, and fails to account for the immense diversity found within each of these pan-ethnic groups. But despite its shortcomings, this classification does not come out of anywhere—it does cover the most widespread hair structures on these populations and answers to a particular set of characteristics and notable differences regarding each.

The characteristics of so-called African Hair.

Despite their vast diversity in appearance and texture, all hair is the same—structurally speaking, at least.

Regardless of ethnic origins, hair is composed of mostly keratin, a particular type of hardened protein that is also responsible for nails. In nature, this protein is also the quintessential component of scales, spider silk, feathers, claws, horns, and hooves.

A study executed at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facilities in Grenoble, France determined, after throughout analysis, there is no biochemical difference in the keratin, amino acids, and molecular gratin structure found amongst all three ethnic hair types. Likewise, all hair types have the same structure—cortex, cuticles, and medulla.

What accounts for the differences in hair appearance answers, mostly, to the follicles they grow out of. Although each person’s hair is unique and answers to exact traits that can vary wildly from others around them, specific characteristics are so widespread within certain races that they cannot be separate from them. The shape, size, and distribution of follicles is one of these aspects.

So-called African hair is defined by having an elliptical, flat, almost ribbon-like follicle shape in cross-section, compared to the rounder structures found in Asian and Caucasian hair. Since the follicle acts as the mold that will shape and determine the width of the hair that grows out of it, it creates a corkscrew, zig-zag pattern that is too thick at the broadest cross-section but relatively thin and fragile in the remaining one.

When it comes to hair density, African hair may seem like a winner, but that is hardly so. Its coiled structure gives volume, but the actual number of hair follicles is, on average, smaller than that of Caucasian and Asian hair.

Likewise, the follicle structure makes hair growth slower compared to other ethnicities, and the zig-zag shape resulting from it can create “shrinkage,” therefore making the hair seem shorter than it is. The hair fiber itself can also come across as “coarse” to the touch thanks to the coil’s folds and the natural dryness of the hair—natural oils from the scalp have a more challenging time trailing down the hair to coat it.

As a result, African hair is coiled and voluminous, although not quite dense. It is delicate, fragile, and prone to dryness.

To classify hair according to these nuances in structure—yet unrelated to ethnicity—Oprah Winfrey’s stylist Andre Walker created, in 1997, the so-called Andre Walker Hair Typing System, which has reached mainstream relevancy in the beauty industry.

According to the chart, the types of hair can be classified into four categories. As such, Type 1 is straight hair, Type 2 is wavy, Type 3 is curly, and Type 4 is kinky-coily. Each of these categories has three subdivisions, identified with a single letter—for example, 4a, 4b, or 4c—denoting the curls’ size or the texture of the hair.

Generally speaking, there is an overlap between the ethnic and hair type classifications. So-called Asian hair is overwhelmingly Type 1, Caucasian hair ranges from Type 1 to Type 3, and African hair is mostly Type 4.

Perfect samples to understand the appearance of Type 4 hair is well-known celebrities and media figures. Actresses Yaya Dacosta, Skai Jackson, and Lupita Nyong’ o are perfect examples of the difference in texture and style between types 4a, 4b, and 4c, respectively.

Naturally, not all Black men and women display Type 4 hair, and not everyone with Type 4 hair is dark-skinned as such. However, there is no denying that there would be an almost universal overlap in a Venn diagram of both groups. In fact, the presence of Type 4 hair can be an overwhelming indication of potential African ancestry, and it can be a matter of discrimination even in white-passing individuals.

In conclusion, talking about Black hair or Afro-textured hair is talking about kinky-coily hair with low density, high volume, and a coarse yet delicate texture, often classified as Type 4a, 4b, or 4c.

The genes associated with this type of hair often indicate strong hints of African ancestry, so talking about Black hair includes biracial individuals and mixed-ancestry folks that may be white-passing but still display the hair type genetically associated with Black people.

It is not just hair.

A slight alteration in follicle shape creates hair types as different as day and night. Despite boasting of the same structure, Afro-textured hair is the most delicate of them all—perhaps even “high maintenance” thanks to the investment it requires.

Delicate and fragile, each of the turns of the distinctive “zig-zag” pattern creates potential breakage points and minimizes the protective oils’ reach emanating from the scalp. As such, Afro-textured hair requires intensive hydration, styling that is entirely different from that of other hair types, and extensive protection against damage through specific hairstyles and products.

In short, the beautiful shape and texture of Black hair come with the downside of frailty. To keep it healthy, effort is required.

Due to this unique combination of factors, Black people developed particular ways to take care of their hair, differing vastly from those found in other ethnic groups. Likewise, the time and resource investment required to protect Afro-textured hair from the elements made haircare an essential social activity and elevated the hair’s significance within each culture.

Black hair is not just hair.

Understanding the biogenetic differences in African hair—compared to other ethnic groups—is essential in comprehending the importance of hair care, beauty rituals, and aesthetics for Black culture worldwide. Afro-textured hair is a symbol of Blackness, as much as skin color is, and it faces the same discrimination, prejudice, racism, and unfair standards.

Therefore, it is quintessential to understand these specificities to follow the journey of Black beauty standards as they relate to hair—through pride, slavery, emancipation, protest, and appropriation.

Black hair is identity and culture, and therefore a matter of pride.

Ethnic differences in hair fiber and hair follicles. Retrieved from https://www.keratin.com/aa/aa002.shtml

Evans, T. (2020). Testing Tactics in Hair: Beyond Biology—Why African Hair is Fragile. Retrieved from Cosmetics & Toiletries at https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/testing/methoddevelopment/Testing-Tactics-in-Hair-Beyond-Biology-Why-African-Hair-is-Fragile-570873421.html.

Franbourg, A., Hallegot, P, Baltenneck, F., Toutain, C., and Leroy, F. (2003). Current research on ethnic hair. Retrieved from the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology at https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(03)00346-3/abstract.

L’Oréal Research (2015) Diversity of Hair Types. Retrieved from Beauty Tomorrow at Medium https://beautytmr.medium.com/diversity-of-hair-types-b3615cec8ed8.

Tecklenburg Strehlow, A. (2005). Interactive questions about African American hair. Retrieved from Stanford at The Tech Interactive: Understanding Genetics at https://genetics.thetech.org/ask/ask107